This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #147, on the subject of Traditional versus Contemporary Music.

I have probably had this discussion with quite a few people over the decades, but the one I specifically remember was Luterano, whom I knew only by that screen name through a small forum sponsored by a Lutheran Bible, book, and gift shop. The short version of the story about what brought me there is that the editor of a now-defunct site called The Gutenberger had read my now somewhat outdated article Christianity, Homosexuality, and the E.L.C.A. and after some discussion invited me to write a piece for them, which was (preserved on my site) In Defense of Marriage, and this was the forum to which he directed his readers for discussion of the articles.

The discussion is about “new” “contemporary” Christian music being sung in churches and worship services, as against the older “traditional” songs found in our hymnals. In these discussions I am usually defending contemporary music against someone who just does not like it, but who couches their dislike in claims that such music is itself wicked. Luterano was different. His view was that contemporary Christian music was simply bad, in the sense of being poor quality. The music was trash, the lyrics pablum, the theology often weak, and the focus usually on the singer and not on God. The songs just weren’t good Christian worship songs.

I should also mention that although I do not actually know anything about Luterano outside our forum discussions, my impression from those was that he was a young Lutheran seminary or Bible college student who was very serious about the Christian faith, but also the Lutheran definitions of it.

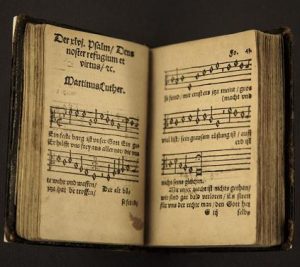

My defense of contemporary Christian music is not that it is better than traditional music. I have a long history with traditional music, and have sung even some of the great works like Handel’s Messiah, Bach’s B Minor Mass, Mozart’s Requiem, Haydn’s Creation, and Mendelsohnn’s Elijah. I have been known to break out into singing selections from some of these quite spontaneously; they are wonderful–and there are many other wonderful pieces that are less well known. I have also sung Ives’ 67th Psalm, Poulenc’s Gloria, Randall Thompson’s Peaceable Kingdom–also all wonderful pieces. However, these are not songs which your average person is likely even to enjoy, let alone be able to sing. As we discussed in web log post #109: Simple Songs, people need songs they can easily learn and sing. That usually means songs with which they are already familiar to some degree. The Reformers knew this, and frequently wrote Christian lyrics for popular folk or drinking songs, many of which are still preserved in our hymnals.

That is, of course, an important point: all “traditional” songs were once “contemporary” songs. They were of a style and manner that was familiar to and comfortable for the people of their time, and they had lyrics which touched something in the lives of those people.

That is also probably why older established churches sing a lot of older “traditional” hymns and newer fellowships tend toward the “contemporary” music. A fairly high proportion of those who attend the established churches grew up in those churches or churches very like them. I know most of the hymns in the hymnal of my present home congregation because they have been in hymnals in Baptist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Assemblies of God, Methodist, and other denominational churches I have attended over the decades, and I learned them. There is perhaps a bit of nostalgia to them; there is, more importantly, a high level of familiarity–if you’ve been singing, or at least hearing, a song since you were in preschool of course it will seem easy to you, while the same song to someone who has never heard it might be very challenging. I love both melodies for Crown Him Lord of All, but I would not say that either is an easy song for someone unfamiliar with it. And it is not simply whether or not the congregant knows this particular song–those of us who have sung barbershop know how barbershop harmonies work, those who have sung madrigals understand the structures of madrigals, those who have sung Bach chorales are familiar with that kind of song, and those who have not sung or oft heard these different kinds of music find them something of an alien landscape to be negotiated with difficulty. If a song is already like songs with which people sing along on the radio, the familiarity of style and feel will make it easier to sing. Many, perhaps most, newer fellowships, contain a lot of people who are new Christians, who did not grow up immersed in churches and singing the songs established denominational Christians have always loved (and let’s face it, even among us there are some for whom In the Garden and At the Cross are those beloved traditional hymns and others for whom the real traditional hymns are Onward Christian Soldiers and Immortal, Invisible, depending on the histories of our own churches and upbringings).

But shouldn’t we be encouraging these new Christians to learn and sing the “good” songs instead of the “trash”?

Well, yes–but how do we decide which are which?

Face it, most songs in any category are trash. Even most of the songs that were the number one songs on the top forty charts in the nineteen fifties and sixties today have at best a nostalgic appeal to people who are sixty and seventy years old. The best of those songs, probably relatively a handful, have a “retro” appeal to today’s listeners. However, in some sense the “best” of them survive the test of time, and are remembered and passed on to the next generation, sometimes redone by a new ensemble.

What makes them best? That’s complicated.

One would like to think that the songs which combine the best music with the best words would be the ones that survive. Regretably that is not so. Many songs which are musically interesting with truly wonderful lyrics die on the vine, as it were, forgotten before they are remembered. For a song to succeed at all, it must primarily touch something irrational in the hearers. People have to connect to the song in some way, and if they do they will sing it or listen to it, and continue to do so for the rest of their lives. And those songs are the ones that capture the attention of the generation–and then it gets complicated.

It gets complicated because at least some of those seemingly great songs are embraced because they capture something vital in that time and place, something unique to those people–and those songs fade away as the world changes away from them. The next generation does not find the same connection and does not keep those songs, and if the generation after that does not revive them, they’re gone. Of course, some songs will capture the hearts of several generations, and they’ll wind up in hymnals being preserved; if they skip a generation they’ll often return. Still, over time they drop from use. Bach is known to have written over four hundred “chorales”, effectively hymn settings; if your hymnal contains five, that’s remarkable.

In fact, in our debate Luterano exclaimed that the Lutheran hymnal contained one hymn from the third (maybe he said fourth) century, as demonstration that there was great music with great words before the modern contemporary material. I observed, though, that we can be fairly certain that during that century Christians sang more than one song during worship; the fact that this one has survived all those generations certainly attests to its appeal to believers across the years, but it also tells us that some unknown number of other fourth century tunes were lost as they were replaced by what were then contemporary worship songs, until only one from that time remained. In the same way already songs from the Great Awakenings are being culled, leaving only those which still speak to us today; songs from the Jesus Movement are vanishing from memory.

The contemporary songs have no better claim over the older ones than that they are contemporary. That means that they have a familiar style and feel. It also means that they speak to many believers where we are in this time. Some of them will continue to speak to believers for another decade, another generation; some might still be in whatever we use for hymnals in a hundred years. Very few will last longer than that–and by then, they will have joined the ranks of the “traditional” music, as a new kind of contemporary music dominates in the new kinds of churches that exist then.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]