This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #117, on the subject of The Prime Universe.

Proofreading some pages I wrote for Bob Slade (character introduced in Verse Three, Chapter One: The First Multiverser Novel) brought a smile to my face. Bob always tickles me; he is written to be fun. In this particular instance he wonders whether something in the universe he is visiting is like it is in “the real world”, and realizes that he still thinks of the earth in which he was born as somehow more “real” than the half dozen universes in which he has lived for more years than he was there. It occurred to me that that might be “gamer-think”, but it seemed like something Bob would ponder. I let it stay.

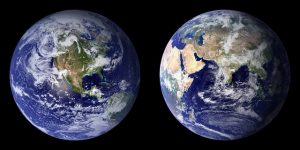

A few days later I was very much enjoying a book by Ian Harac (those of you who follow my Goodreads reviews will undoubtedly read about it there in a few days), a sort of multiverse story in which the lead characters are investigating inter-universe smuggling, and one of them referred to their universe of origin as “earth prime”. It struck me then: how does a culture that travels the multiverse define a concept like “earth prime”?

If you believe in the sort of diverging universe theory in which for every choice the universe divides into two universes, one in which that happens and the other in which it does not (I do not), you might think there is a simple answer: the “prime” universe is the root one from which all others diverged. That, though, does not work. Let us suppose that at the dawn of human history a hypothetical Cain is faced with the choice of whether or not to kill his hypothetical brother Abel. By this theory, our universe splits into two, one in which Abel is killed by Cain and the other in which they are both alive. Which is the prime universe, and which the divergent? Obviously, you suggest, the one in which Cain took the action to kill Abel is the diverging one, because Cain did something that changed history. That’s not true, of course: Cain did something that created history, as there was no history of that moment prior to that moment. Further, although we have so viewed it, it is not as if it is a choice between killing Abel and not killing Abel. It is rather a choice between killing Abel and doing something else instead. He could have gone back to work on his garden; he could have left to have a chat with his mother; he could have asked his brother to teach him to raise sheep. If we are in the universe in which Cain killed Abel, to us it appears that those are all divergent universes; yet if we are in one of those, it is the death that is the divergence, or one of the divergences. We might think that the death is the most dramatic or drastic version of history, but that is very much our ego: why should killing one man be a more significant event than giving life to thousands of vegetables and their offspring? It assumes the importance of humans.

I agree that humans are more important than vegetables, but in the scheme of a godless diverging multiverse that can’t be more than a personal preference.

Thus in a sense, if all universes diverged from one original, all have claim to be that original. If you cut an earthworm in half, both halves regenerate giving you two earthworms; both of them are the original. Every amoeba having come into existence by the cellular division of an amoeba in which one becomes two is the first amoeba that ever lived, from its own perspective. Every universe that is viewed as diverging from another can itself be viewed as the original from which the other diverged, and that is the reality from the objective outside view. There is no “prime” universe in that sense.

Of course, there are other theories of the multiverse. Some hold that all the many parallel universes have always existed, either eternally or from the beginning of time. No such universe can claim to be “first” in a temporal sense. Yet often one is still identified as “prime”.

Let us remember that the suggestion is made that there is an infinite number of such universes. I find that absurd, but concede that if the notion of parallel universes of this sort is true there might well be more universes than there are stars in our own. Vast becomes too small a word.

Something distinguishes each universe in this multiverse. Whatever it is, if we are to become able to travel it in a controlled fashion we have to discover it and turn it into something quantifiable. Thus if every universe has a “frequency” at which it “vibrates”, we can give every universe a number equal to that frequency–akin to radio stations, each of which is identified by the number of cycles per second (renamed to honor a scientist named “Hertz”, changing the abbreviation from c.p.s. to hz.). Of course, it is unlikely that universes “vibrate”, but there would have to be some measurable and quantifiable distinguishing factor, something akin to coordinates, for which we could make a scale.

Making a scale is the problem–not that we could not make one, but that any scale we made would be arbitrary by definition. Inches and feet are only “real” because we have agreed definitions. The metric system prides itself on being scientific, every unit defined in relation to every other unit, but ultimately the basic unit, the meter, even though it is defined by other scientifically determinable values, is still arbitrary. The unit of time we call a second is one sixtieth of one sixtieth of one twenty-fourth of the average period of rotation of this planet from sunrise to sunrise over a year–fundamentally arbitrary and not so constant as was once believed. So we might think that the “prime” universe is the one in which the measured value of the vibrations is “one” on our scale, but our scale is arbitrary. As with the number of “gravs” as a measurement of the gravitic force of other planets, we arbitrarily assign “one” to our own planet and measure the others against that.

Perhaps, though, we could make the “prime” universe that one with the lowest “vibration” (or the highest–it is the same result). The problem here is that, assuming “zero” is not a possible reading (all universes by this definition must vibrate, and “zero” constitutes not doing so) and given the incredible number of such universes, we could never be certain that we had found the universe with the lowest frequency and so could not know which universe was “prime”. We might devise a formula which determined a theoretical lowest possible frequency for a universe; the formula would very likely be incorrect, and we might not be able to determine whether a universe with that value actually exists.

So then the prime universe is decided arbitrarily, and the best choice would be that universe which first determined how to travel to the others. We would label our universe “prime” and measure all the others by their relationship to us; our “frequency” would be “one-point-zero-zero” out to however many places seemed necessary for accuracy, others measured by variation from that.

However, the odds are fairly slim (what am I saying? they’re infinitessimal) that our universe would be the first to discover how to travel the multiverse. Further, given the hypothetical vastness of the multiverse it might be a thousand, a million, a billion years–even never–before we encountered a world which had independently learned to do what we do (unless of course by some wild chance they found us before we solved the problem, but then they have the same problem): which universe gets to be “prime” because they discovered this first?

Ultimately, then, we call our universe “prime” if we invented our own way of traveling the multiverse, not because that has any meaning other than that we regard it our original home. If someone brings the technology to us from another universe, in all likelihood we will call their universe “prime”, and ours will be defined on the scale they devised. It seems the word has no meaning other than “that universe we have chosen as the one by which our scale is calibrated”. If there is a multiverse of this sort, there is no “prime” universe by any other meaning.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]