This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #73, on the subject of Authenticity of the New Testament Accounts.

I have covered–or perhaps I should say I will be covering–this in my hopefully forthcoming book Why I Believe. However, I recently read a work of fiction in which a widely embraced and repeated nineteenth century error was asserted, not once but twice, not casually but in the presence of a person trained in a presumably conservative seminary who instead of knowing better and saying so accepted the mistake and was significantly motivated by it. The mistake is that the New Testament documents are not historically reliable, and specifically that the Bible contains four Gospel accounts written long after the first century pseudepigraphically (that is, by anonymous authors who took the names of famous persons), to tell the story the Church wanted at that point to tell.

There are so many problems with this view that it is difficult to know where to begin; however, the core problem is that attitude that the New Testament Gospels, which include the resurrection of Jesus, are not authentic historic accounts.

The root of the problem is a circular argument that was the basis for a lot of what passed for nineteenth century scholarship: miracles do not happen, and so we need to figure out why certain documents related to the Christian faith report that they did. The obvious answer was that despite the fact that the church had always believed these documents were written by first century eyewitnesses or investigators, they were actually written centuries later by church leaders attempting to create a history that supported the religion they wanted. At the same time, there were competing Christian sects which wrote their own similarly pseudepigraphal accounts which presented a different view of Jesus, which are just as valid–which is to say just as invalid–as those generally accepted. The support for this theory is simply that it provides an adequate explanation for why accounts claiming to be, or be based on, eyewitness testimony report events we want to say never occurred: the claims of historicity are invalidated by the late dates.

The fact that that is a circular argument is lost on most people, because most modern people buy the premise: miracles do not happen, and therefore any account that claims miracles did happen must be false, and it’s just a matter of finding a plausible explanation for how such a false account could have been accepted as true. That in turn is aided by the modern view that our forefathers were gullible idiots who believed many impossible things simply because they lacked the intellect for modern science. The people who think this have never wrestled with the towering intellectual works of Augustine and Athanasius and Tertullian; they simply assume that people who believed in miracles must not have been very smart, because they don’t believe in miracles and have an inflated view of their own intellectual capabilities, and perhaps more defensibly because they know some other truly intelligent people who don’t believe in miracles. Yet the events recounted in the Gospels are reported not because the writers thought miracles happened all the time, but precisely because the writers recognized that these were violations of the natural order, that events were occurring that ought to be impossible. Our ancestors, and particularly the writers of these books, did not believe in miracles because they were gullible, but because the evidence available to them on the subject was overwhelmingly credible despite the seeming impossibility.

Let’s set aside the fact that the accounts read like eyewitness testimony. There could be explanations for that–it is likely that at least parts, and sometimes substantial parts, of the Gospels themselves were compiled from source materials, short eyewitness accounts that had been put to paper before the Gospels themselves were composed. This theory explains the kinds of similarities and differences we have, particularly between the three “synoptic” Gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke. At least part of their work involved compiling the earlier recorded accounts of others. This, though, makes the accounts more, not less, reliable, as it suggests that the accounts were earlier than the Gospels themselves, and the Gospel writers selected those they thought most credible at the time. We think that it is possible to invent something that sounds like an eyewitness account, filled with unimportant details, but such fictional accounts were unknown then, and certainly never attempted to report anything resembling historic events. That is a feature of modern fiction not known in a time when things were written because they were important to someone.

Also, we must dispel the notion that the claimed writers were ignorant peasants who could not read nor write. Luke is identified by Paul (we’ll get to him) as a “healer”, the word commonly taken to mean doctor, and the educated use of the Greek language in the two books attributed to him reflects that about him. Matthew was said to be a tax collector, and it is unlikely that the Romans would have given the responsibility to assess and collect local taxes to someone who could not read and write. What little we know about Mark suggests that he was the son of a wealthy Jewish family–Barnabas was a close relative, probably an uncle, and a propertied businessman. The possibility of a wealthy Jewish boy not receiving an education in that era is non-existent. People will claim that John was a poor peasant fisherman, pointing to places in the world in modern times where uneducated peasants eke out a living by lakesides. However, John was co-owner of a fishing business (with his brother James and their friends, the brothers Peter and Andrew) which had employees, several boats and ample equipment, and was prosperous enough that the four owners could leave it in the care of their employees for most of several years while they took a sabbatical to learn from an itinerant teacher–and note that Peter, at least, had a family that would have to be supported by that business in his absence. Our image of the peasant fisherman should be replaced by the image of a fishing magnate. They were the Mrs. Paul’s, the Gorton’s of Gloucester, in their time. They weren’t independently wealthy, but their business holdings were adequate to support them and their families while they took a couple years away from work. They, too, were almost certainly educated; Jewish boys became Jewish men by proving at the age of 13 that they could read the Torah, Prophets, and Writings in public. To think that they could not also work in the commercial language of the age is silly.

Besides, even very well educated persons, such as Paul (son of wealthy businessmen in a Roman city, student of one of the top Rabbis of all time), frequently dictated letters and books to a scribe, called an amanuensis, in the same way that twentieth century executives and authors dictated letters and books to stenographers (or later Dictaphones) to be typed, to ensure a clear and legible copy. They did not need to write well physically to be the authors; they only needed to be able to tell the scribes what to write.

So these purported first century authors could have written these books; the more significant question is, did they?

To that, we have testimony as early as the end of the first century–Clement of Rome, writing c.90-110 AD, who asserted that there were four recognized accounts of the life of Jesus. By the middle of the second century those four accounts had names, the same names as the books we have. That testimony spreads across the Roman Empire, coming from sources in Alexandria (Egypt), Antioch (Syria), Smyrna (Turkey), Carthage (North Africa), and Rome (Italy), and from people who apparently had, and independently preserved, copies of them. It is impossible to argue that these documents were not well known by the beginning of the second century, and almost as difficult to argue that the persons preserving them, separated as they were by long distances and relying on the documents to preserve the truth they believed, would have agreed to change them. The hundreds of ancient copies of portions of the New Testament which we have today are traced back to origins in those diverse regions; they are the best attested ancient historic documents in the world.

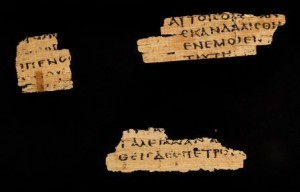

There are also early fragments of these same books. The ones pictured above in this article, sometimes called the Magdalen Fragments because they were stored at Magdalen College, more recently called the Jesus Papyrus, have recently been dated to sometime around fifty or sixty AD–the middle of the first century. They show fragments of the Gospel of Matthew on both sides. That makes them the earliest known extant copies of any part of any New Testament book–yet it is significant that they are copies, clearly showing evidence that they were copied from a previous version, and thus that the book was already in circulation and being copied and shared across long distances. A well-known early first century original is thus virtually certain, based on this scholarship.

Yet even if we suppose that somehow they actually are later documents, that does not resolve the problem for those who deny the resurrection. You still have to deal with the letters of Paul. No one doubts that most of his letters to churches were written by someone of his name and description in the mid first century. In almost every one of them the author reinforces the notion that Jesus arose from the grave, that that is the essence of the message; in several he asserts that he is one of the witnesses who saw Him, and he also tells us that he had met other witnesses, of which there were over five hundred.

The essential element of the Christian faith, that Jesus Christ was executed and arose from the grave, is incontrovertibly historically supported. It is of course possible that it is not true–as it is possible that George Washington was not the first President of the United States, that Hitler did not run concentration camps in which Jews were exterminated, that Sir Isaac Newton did not create the famous laws of motion that are known by his name. Everything that is historical is open to question on some level. We evaluate the evidence and reach conclusions; we do not reach conclusions and then use them to discredit the evidence.

I hope to have the book available soon. It goes into more detail on some of these issues and many others. Meanwhile, don’t believe the disbelievers without examining the evidence.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]