This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #129, on the subject of Eulogy for the Record Album.

The record album is, if not dead, dying. This relatively short-lived art form has fallen from popularity, and may soon be as forgotten as the vinyl long-play record that made it possible.

It might be useful to recount some of the life of this entity. We touched on this in web log post #111: A Partial History of the Audio Recording Industry, but we’ll review relevant portions of that and continue with what is specifically of value in connection with the record album. Originally, Thomas Edison’s recordings were one song per cylinder, but when his competitors forced him to move to disks they became one song per side. Over time, as we described, we reached the point where a long-play twelve-inch vinyl disk running at thirty-three and a third revolutions per minute could put almost half an hour of stereo music on each side. (There were a couple of quadraphonic albums made, but the technology failed to become popular.)

Initially a record album was probably not much different from a photo album–a collection of pictures whose only connection is that the same person took them, probably around the same time and place. Even with early pop-rock albums, this was still the case: early Simon and Garfunkle records are good examples of this, a collection of songs which are together only because Simon and Garfunkle recorded them. However, gradually something else emerged: the album as an art form in itself.

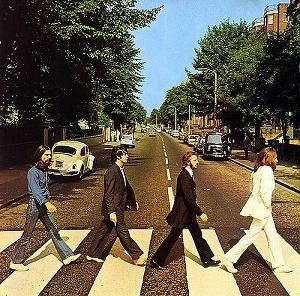

It was inevitable that it would happen. Album art was becoming a major concept, as the twelve-inch square covers were a wonderful size for creating interesting images, and the interesting images were part of the marketing of the album. Yet more thought went into creating albums not so much as collections of separate songs but as performance programs in themselves. Albums like The Beatles’ Abbey Road and Tommy by The Who are prime examples of this, in which the songs connect together to create an impression, even a story. Not every album was done this way, but it was becoming enough of the norm that it was the expectation: the album itself says something, and was intended to be heard in its entirety, each song introducing the next, following from the one before, from a starting point to an ending point much as a symphony or an oratorio.

Indeed, when we went into the studio to record Collision: Of Worlds, one of the points I made was that we were recording an album, not a demo. The songs should be arranged so that they created a cohesive whole. With a demo, you put three different songs on the disk representative of your range of style and know that you’ll be lucky if the target audience ever hears the second; you can put four, but the fourth probably won’t be heard unless the first three are truly impressive and show a range of style that warrants saying you do more than just those first three songs. With an album, though, the transitions should be smooth, the story should advance with each song, it should all be told one step at a time. The listener should come away at least feeling as if there was a message.

That doesn’t always happen, particularly in the hamburger mill in which record companies pressured bands to create new albums. Artists sometimes went into the studio with no idea what they were going to record, and wrote the music while they were there–resulting in disjointed and uneven collections of compositions and performances which they then tried to promote as something meaningful. Critics often complained that such albums contained one good song which was popular and ten or eleven others that were created as filler so there would be an album, and that complaint was sometimes valid.

Sometimes valid–but not always. For one thing, artists almost invariably have great difficulty evaluating their own material. It is known that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle hated Sherlock Holmes. I can tell you which of my songs have the most meaning to me, which most impress me musically, which were the most challenging to write–but I can’t tell you which ones have the best audience appeal or are the most popular, generally. That is, the songs I think are “good” are not necessarily the ones the audience likes.

That’s complicated by the aspect of popularity. We’ve cited this before: what makes a song popular is the appearance that it is popular. Most people like the songs they think their friends like. It’s more a social phenomenon than a measure of quality. Many “singles” were released in which no one knew which side would get the airplay and become popular, but only one side did–the other was called the “B side”, and most people were completely unaware of what songs were on the flip side of most of their favorites. The fact that a song is or is not popular cannot be a gauge of whether it is any good, in large part because no one could have known whether it would have been popular prior to its release, and in large part because popularity itself is not a measure of what is good.

Why does any of this matter? The new marketing technology now has it arranged so that you can buy any song you want from any album, and ignore the rest of the album. If you want a copy of Colour My World from Chicago’s self-titled second album (the first was Chicago Transit Authority, the second Chicago, sometimes called Chicago II for clarity), you can buy it and not get Make Me Smile or 25 or 6 to 4. And that becomes the problem on several levels. One is that albums often contain many good songs you will never hear because you bought the one song that you did hear. Another is that you take the songs out of context–both Make Me Smile and Colour My World are part of what was called a “song cycle”, seven titles that formed a story unit within the album, but most people don’t know that and don’t know the other five songs because these have been excerpted from their original places. Another is that you might like those songs you’ll never hear–and even if you don’t like them today, if you bought the album and listened to it you might discover that next week, year, decade, a song which meant nothing to you at the time now has significant meaning to you. The first time I read The Chronicles of Narnia, what was originally the fifth book (now usually listed as the third), A Horse and His Boy, did not impress me. A few years later I read the series again, and suddenly the imagery of Aslan having guided what seemed ordinary coincidental events to bring the right person to the right place at the right time to save his people rang so true with me that it quickly became my favorite entry in the set. The fact that a song on an album does not catch your attention the first time through does not mean it’s not a great song that’s going to touch you deeply at some moment in the future, and you deprive yourself of that possibility by ignoring the songs on the album that aren’t your first choices today.

Besides, the concept of the album as a unit is part of the artist’s effort to convey his message.

I was on the air at WNNN-FM when Dan Peek released his first solo album, All Things Are Possible. Peek was one of the founding members of the band America (Horse With No Name, I Need You), and it had become known in the Christian music industry, at least, that he had long prayed that if God allowed him to become successful with the band he would use that fame as a platform to declare his Christian faith. The title track from All Things Are Possible has potential in that regard: it was rising not only on the Christian charts but on the pop music top forty as well.

When I interviewed Peek, though, I asked him about whether he had any concerns about the fact that his song, whose title was drawn from the New Testament to suggest that Jesus made the impossible possible, was being embraced as a popular love song, and particularly among homosexual couples. He agreed that it was possible to hear the lyrics–All things are possible with you by my side; all things are possible with you to be my guide–and miss the intended meaning, but that certainly anyone who listened to the album would know what it was about. The true meaning of the song was, to some degree, dependent on whether the listener had heard it in its intended context. What the artist was trying to say was not coming through to millions, because they heard what they wanted to hear, not what he wanted to say.

There is a degree to which the listening audience perhaps does not care. If I like a song, I like it for what it means to me, and not for what it was trying to convey. Yet that attitude does the artist a disservice. The people who create communicative art do so to communicate, and if I’m not listening to what they’re trying to say, I am ignoring them and abusing them. If someone has created something I have enjoyed, do I not owe it to that creator to understand why he did it?

Yet this death was inevitable. When the MTV cable television channel went on the air, its first song was Video Killed the Radio Star, and it seems that it has moved beyond that such that the Internet has killed the record album. Even many of my acquaintance who are serious about the music to which they listen don’t acquire albums or listen to them, preferring to compile their own favorites lists–easily done, and you only hear the songs you’ve already decided you like without having to listen to songs that did not appeal to you the first time you heard them. We can say that the music industry lost something, but perhaps now artists will focus on producing individual songs that appeal to our short attention spans instead of major works that call us to invest something in the bigger picture.

I will miss the album, despite the fact that I have never been wealthy enough to afford to buy more than a few over the decades. As a musician, though, I will have to adapt to the return of the what I thought antiquated singles market mentality, and focus on single songs instead of collections.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]