This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #111, on the subject of A Partial History of the Audio Recording Industry.

In a previous post, #109: Simple Songs, I said that I had some criticism of Christian record companies that I would defer to another article. This is that.

I avoid criticism, generally, so I am approaching this more as an attempt to understand and explain why things are as they are, that is, how they got that way, by going back decades and looking at the relationship between the artist and the recording company and a few other entities that were involved in that relationship.

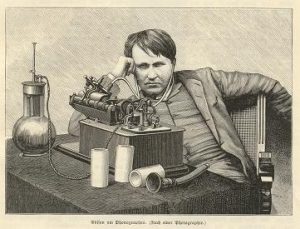

Audio recording of course began with Thomas Alva Edison, who invented the phonograph and subsequently founded the first record company. His early recordings were cylinders; his competitors forced him to change to disks, which had worse fidelity but were easier to store and use. They spun seventy-eight time each minute, were usually ten inches in diameter, and had one song on each side. I have little knowledge and less experience of that time, so I can’t tell you too much about it other than that there are some recordings of a few nineteenth century musicians which have survived. The invention of audio recording was followed by motion pictures and radio, both of which impacted the music business. In the early days of radio, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) objected to broadcasters airing prerecorded music, except in the case of concerts that were aired live but recorded for rebroadcasting later. Then beginning in the nineteen fifties television began its ascendancy, and the FCC was considerably less interested in radio; record companies saw this as the opportunity to sell records by getting airplay, and the connection between record companies and radio stations became the lynchpin of the music industry. (This was the age of “payola”, when record companies paid people to air their records, recognizing intuitively what was later demonstrated scientifically: that what makes a recording popular is the perception that it is popular.) Recording technology improved, such that it was possible to put more information on a disk by using narrower grooves and more sensitive needles. This gave us the Extended Play (EP) disk with two or three songs per side, the “forty-five”, a smaller seven-inch disk that ran at a slower speed, and eventually the Long Play (LP) album, which ran at thirty-three and a third turns per minute and squeezed over twenty minutes on each side. Along the way, better needles began to be able to detect and distinguish vertical as well as horizontal vibration, and stereo records took over.

At this time, record companies tended to buy a recording outright. It was possible then to use a small quarter-inch width seven-inch-per-second tape recorder with one microphone and record a single which had the potential to become popular on radio stations and sell a lot of copies. The model in the book publishing industry had long been that a publisher paid an author for the right to print a specified number of copies of his book; the risk was then on the publisher to bet that he could sell that many at a price that would recoup his investment. Copyright law arose to protect publishers, and indirectly authors, from others printing copies of books for which those others had not paid anything–but it did not cover audio recordings. Thus once a record company had paid for the right to sell the recording, all the proceeds from sales went to the record company, but there was no protection against “song piracy”.

This changed in the sixties, for a couple reasons. One was that copyright law caught up with technology, and it was possible to protect an audio recording separate from the songs it contained (previously only covered as songs when they were printed and sold on paper). Now there was a shift toward revenue sharing–the artists began to get a percentage of the gross. However, they signed recording contracts, which in essence meant that they worked for the recording company–they had to perform concerts as directed by the company, record and perform the songs the company said they should, and produce product on schedule. Even The Beatles had to record songs which were not theirs, because the recording company thought they would sell.

The next big change is generally agreed to be the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The Beatles were by that time a phenomenon–they probably could have reached the top of the chart with a recording of the four of them snoring. They told the record company that they would sign a new contract and make another record if, and only if, they had full creative control of it. With trepidation–after all, the company thought they were the professionals who knew what would sell and what wouldn’t–the company agreed, Sgt. Pepper’s was a huge success, and thereafter music aimed at the youth market (about thirteen to thirty) included giving creative control to the artists, on the assumption that they were all young and in touch with what the young wanted to hear. Record sales of successful musicians were good, and companies had capital to spend on new artists (which would be money lost if the artist failed). Records made a lot of money, and record companies put a lot into promoting them. Concert tours were in essence promotional efforts to sell records: a band would lose money on the tour in order to make it back on the sales of records, and the company paid part of that cost.

However, as technology advanced in the recording industry, the demand for quality increased. No longer could someone record a hit single in his garage. Chicago‘s song Twenty-five or Six to Four was about paying for recording studio time when it was twenty-five dollars an hour or twenty-five dollars to use the studio overnight, plus the cost of recording tape–and three-inch width recording tape at fifteen or even thirty inches per second was not cheap, but it was only the beginning. By the late seventies and early eighties, recording studios that produced the kind of quality product record companies wanted cost sometimes thousands of dollars an hour, and it took many hours to lay the tracks, check them, re-record problems, do the mix, and process the final product. Vinyl was a petroleum product, as were most of the substances used for recording tape, and with the appearance of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) these were becoming more expensive. The cost of making a record was rising; the profit from selling one was falling. Record companies were paying a lot of money in promotions and advertising. Contracts started shifting away from percent of gross to percent of net, so that artists would not get paid for their recordings until the company had recouped all the expenses.

In the film industry contracts for major headline actors sometimes include a percentage. Ed Asner (once President of the Screen Actors Guild) has been quoted as saying to make sure it is a percent of gross, not a percent of net: the major studios have a system by which a movie never makes any money, but always owes the studio for production and promotional costs. The same thing has been happening in the recording industry. If you sign a contract today, it usually says that you will be paid once all the costs of producing and promoting the album are covered, but those costs include printing copies, buying advertising, shipping product, and paying the salaries of everyone involved at the company. As the return on investment on records fell, the balance shifted: by the early nineties, concert tickets were outrageously high because artists got no money from selling records, and thus making a record for them was a way of promoting a concert tour. By the dawn of the third millennium, record companies were being hit by file sharing–and many artists did not care, because they never expected to make a dime from their records and file sharing brought people to their concerts. Record companies compensated by changing the terms of contracts so that the record company owned all rights to all performances by the band, and could get a cut of the concert income. Artists often find themselves very famous but not very wealthy.

Meanwhile, record companies are struggling because the model has changed drastically at the sales end but has not caught up at the production end. Artists still think in terms of recording albums; the majority of consumers don’t buy albums, they buy tracks–if they buy anything at all, rather than pirating copies from YouTube® videos and file sharing programs. The quality that goes into making these now digital recordings is in the main wasted on an audience that listens to low quality recordings on low fidelity equipment.

The impact on the Christian market has been somewhat less, because Christians tend to do less pirating and are more likely to buy whole albums of bands they follow. However, Christian record companies have not escaped the crunch despite the rising popularity of Christian contemporary music. A recording contract is no longer a mark of success in the music world; in many cases it’s a badge of slavery. It buys you a lot of help with promotions, but at a very steep price. It is probably the right choice for some musicians, but is becoming less and less so as it becomes more and more possible to produce your own recordings and promote and sell them over the Internet without such professional assistance. The main things that a recording contract gets you are funding for production which you will have to repay, and possible radio airplay which only happens for a few.

The problem with Christian record companies is that they are becoming obsolete and see no clear path to reinvent themselves. I have no advice on that, I’m afraid, despite having worked in Christian contemporary music radio and done some recording myself. The world changes and old industries fail; it is doing so now.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]