This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #172, on the subject of Why Not Democracy?.

As I was writing the previous web log entry, #171: The President (of the Seventh Day Baptist Convention), I was reminded that we, in the United States of America, do not live in a democracy. We live in a representative republic.

That fact was brought home to a lot of people in the recent Presidential election, some of whom are still reeling from it. I have heard many complaints, mostly from young people, that our elected President did not win the majority of the voters, and therefore does not represent the majority of the people. (It is at least worth mentioning that the actual vote totals will never be certain: the vote count was never completed in quite a few voting districts because the total would not have changed the Electoral College outcome in those states.) We should, they insist, change to a more democratic system, in which every vote counts the same.

We could do that. Things are a bit more like that in other countries, particularly Israel where everyone votes for whatever parliamentary representatives they want and the entire country is treated as a single district. Even England’s system is more democratic than ours. However, note that in these countries the voters do not vote for their chief executive–they vote for their legislative representatives, and these in turn choose the chief executive. Sure, British Prime Minister Theresa May campaigns for the position, but she does so by touring the country telling voters to support their local Conservative Party candidates for Members of Parliament, who in turn vote her into the Downing Street office. It is still not strictly democratic, although by taking the vote for head of government away from the people and giving it to their elected representatives it actually becomes a bit closer to it. However, it still can produce the outcome that the party in power, and thus the chief executive, did not actually have the majority of the votes. It is a flaw of representative government, but representative government is the only way to avoid having every citizen in the country vote on every law.

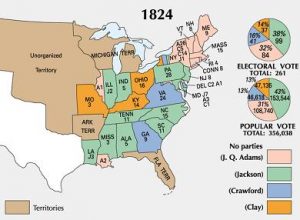

There are, of course, other ways to achieve a more democratic election of the President of the United States. People have been complaining about it since at least the 1824 election, when the failure of Andrew Jackson to gain fifty percent in the Electoral College resulted in John Quincy Adams, with less than a third of the vote, being selected for the office by the House of Representatives (the only time in history where no candidate obtained fifty percent of the Electoral College vote). Some years ago when we were examining the Electoral College in detail in connection with Coalition Government, we noted one suggestion, that each state allocate its electoral votes based on the percentage of voters supporting each candidate–and why that would never be enacted. More recently, someone proposed that states begin changing their system for apportioning electoral votes such that the votes within the state were irrelevant, that each state would give all its electoral votes to whomever won the popular vote nationally. That would achieve the desired “democratic” outcome. It would prevent situations like that of the recent election. The question is, do we want that?

The first point that should be recognized here is that the majority always wants the democratic system. That’s because in a democratic system, the majority can always impose its will on the minority.

Of course, that often happens anyway–but many great strides forward in these United States have happened precisely because minorities were empowered. Certainly it is sometimes the case that majorities become entrenched, resisting necessary change until overwhelmed as public opinion shifts, but it has also been the case that minorities have used the system to gain a voice within the process. There is something called the tyranny of the majority, when minority voices and positions are overwhelmed and trampled by majority opinions. Our system was designed in part to prevent that. There is also a tyranny of the minority, when a small group prevents the majority from doing what it deems right through legal intervention, and our system is supposed to prevent that, as well. Our system produces gradual change by trying to keep everyone somewhat satisfied. Younger people are less patient, wanting rapid change. Older people have usually learned that not all change is for the better, but all change has unintended consequences. Our country advances a bit, then eases back, then advances again, feeling the path carefully.

Many other countries have suffered from what we might call “rapid cycling”. Because they are so controlled by the majority, and because the majority is mostly in the middle shifting a bit to one side and then to the other but the politicians tend to be at the extremes, it is common for one party to be voted into office, make major changes to everything, upset the bulk of their constituents who only wanted things to change a little and don’t like the unanticipated parts, and so be voted out of office and replaced by an opposing party which proceeds to repeal everything the first party did and pass its own extremist programs, leading to its failure at the polls and the return of the original party, or often yet another party, whose agenda then dominates. Remember, as we have often mentioned in connection with coalition government, we are not in our chosen parties because everyone in those parties agrees with us on every point; we are there because we have agreed to support each other on those points each of us think important. That means some of the things you want your party to do other members of your party strongly oppose–the Progressive wing of the Democratic Party wants open borders, but the Labor wing definitely does not; the universal healthcare driven through by the Democratic Progressives has gone very badly for labor unions, whose members lost much of their superior healthcare benefits under the program. Majority opinion is more fickle than a twelve-year-old girl’s crushes. Democracy leads to such rapid changes. People think they want one thing, but when they start to see where that leads, they change their minds and want something else.

Our system does not always give us stability. In recent years the fracturing of political opinion has led to some very unstable situations. However, rapid change is always unstable, and we have seen much rapid change over those years. The system is working to slow the change, to keep things at a pace people can accept.

A more democratic system would not be a better one.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]