This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #190, on the subject of Praise for a Ginsberg Equal Protection Opinion.

To read the conservative press, you would think that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, in writing the majority opinion in Sessions v. Morales-Santana 582 U.S. ____ (2017), had turned her back on women’s rights and struck a blow for men. Yet even from that reporting I could see that Ginsberg was simply staying true to her principles of equal protection (we had discussed her commitment to this previously in web log post #63: Equal Protection When Boy Meets Girl). Still, from the sound of it, I thought she ought to be commended for this consistency even when it seemed to go against her more feminist views.

However, unwilling to write about a court opinion I had not read, I took the time to find it and read it (link above to the official PDF), and found that it was a considerably less impressive story even than I had supposed.

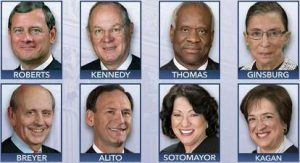

I should perhaps have been tipped off by the fact that the decision was effectively unanimous–seven of nine Justices joining in the majority opinion, Justice Thomas writing a concurring opinion in which he agreed with the result but thought the equal protection language went further than necessary to reach it, and the new Justice Gorsuch not having heard oral arguments not participating in the decision. The court did not consider it controversial. They did, however, overturn part of the decision of the Second Circuit Federal Court of Appeals, so apparently there was a difficult issue in the matter.

It is also of some interest to us because although couched as an immigration case it ultimately proves to be a citizenship case, and we have addressed the statutes and cases involved in whether or not someone is a natural born citizen in connection with The Birther Issue when it was raised concerning President Obama, and more recently in web log post #41: Ted Cruz and the Birther Issue. The terms under which someone is, or is not, born an American citizen are sometimes confusing. That was what was at issue here.

Morales-Santana was arrested in New York on a number of relatively minor charges, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service decided to deport him to the Dominican Republic, claiming that he was not a United States citizen. That was where the story started to get interesting. It seems that the Respondent’s father, José Morales, was an American citizen, having been born in Puerto Rico, and having lived there for almost nineteen years. Twenty days before his nineteenth birthday he moved to the Dominican Republic to accept a job offer, and soon moved in with a native Dominican woman. She gave birth to the Respondent, and the father immediately acknowledged paternity and shortly thereafter married the woman, making the child a member of his household. Everyone assumed the child was an American citizen like his father.

However, the statute defining whether an unwed U.S. citizen father confers citizenship on his out-of-wedlock child specified, among other things, that the father had to have lived in the United States or its Territories or Possessions (Puerto Rico qualifies) for at least five years after reaching the age of fourteen. José Morales, having left Puerto Rico less than a month before his nineteenth birthday, fell short of that requirement by twenty days. Therefore he himself was a citizen, but his child, born abroad out of wedlock to a non-citizen mother, was not.

Morales-Santana, however, recognized a flaw in the law. Had the situation been reversed–had his mother been an American citizen who bore a child out of wedlock with a non-citizen father–the statute only required that such a mother have been in residence for one year following her fourteenth birthday. That meant, Morales-Santana argued, that women were being given a right that was being denied to men, in violation of the Equal Protection rights as understood by the United States Supreme Court.

The Second Circuit Court agreed, and decided that the citizenship conferred on children of unwed mothers ought equally to be conferred on those of unwed fathers, and stated that Morales-Santana could not be deported because he was, in fact, a United States citizen.

The government appealed, resulting in this decision.

What Ginsberg tells us is that the anomaly in the statute is the exception for unwed mothers. The five year rule applies in all other related cases–not only unwed fathers, but married couples in which either spouse is an American citizen and the other is not. If the Court were to rule that the unwed mother status applied equally to unwed fathers, it would have to rule that the same status applied in all these cases–but the legislature clearly intended that the five year rule would be the norm, and the one year rule a special exception for pregnant unmarried girls. They would essentially be discarding the entire statute in favor of the exception. Instead, they ruled that the one year exception was unconstitutional–a ruling whose only effect on the Respondent was that he could not claim citizenship through his father based on the inequity of a rule covering mothers but not fathers.

So Ginsberg certainly did strip some women of a statutory right, but she deserves to be credited for doing so consistently with her express view of equal protection. Asserting that men and women should be treated the same does mean that sometimes women will be treated worse than they otherwise might have been. This is one of those cases; it otherwise is not that important.

As a footnote, the court notes at one point that the statute asserts that a child born out of wedlock whose father acknowledges him and takes responsibility for his care will be regarded a citizen from the moment of his birth. That is relevant to our discussion of what it means to be a natural-born citizen.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]