This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #21, on the subject of Genetic Counseling and Eugenics.

Quite a few years ago now I knew a girl, a childhood friend of my wife, who married a man with Crohn’s Disease. Not long after the wedding she had a tubal ligation, and they bought a dog to pamper. The explanation was that Crohn’s is genetic, and her husband did not want to bring a child into the world who would suffer what he had suffered.

This kind of decision is made all the time. It is called genetic counseling, when medical professionals evaluate the probability that a couple will pass a genetic disease to their children. Sickle cell anemia is one of the most common of such maladies, and many black families forego having children to stem its transmission.

People want babies. It’s part of being human. However, it is also part of being human that people want healthy babies. Obstetricians have the highest malpractice insurance rates of all doctors, because imperfect babies are born and horrified parents want to blame someone with a lawsuit. Modern technology has made it easier to have perfect babies. The parents who might be carriers of sickle cell can have their unborn child tested in utero, and if the child has the disease, it can be aborted, never forced to live with the pain of this crippling disease. The same can be done for Crohn’s Disease, Spina Bifida, Down Syndrome…or can it?

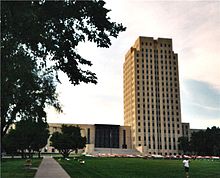

North Dakota has made it illegal to perform an abortion based on detected fetal abnormalities. Ohio is likely to pass a similar law banning abortions performed because the unborn child has Down Syndrome. To those who support abortion, these laws, described as acts to protect the handicapped, are outrageous impositions on a woman’s rights. Yet there is something to the argument.

Although statistics are difficult to determine with any accuracy, everyone agrees that the majority–anywhere from sixty to ninety percent–of unborn children diagnosed prenatally with Down Syndrome are aborted in the United States, and that the estimated rate is higher in Europe where it might reach ninety-five percent. Some parts of the world applaud this as a reasonable means of wiping out a genetic disease. To some, the termination of pregnancy because the unborn child has a serious genetic defect is considered one of the best reasons for such a decision.

What, though, can be more discriminatory against the handicapped than killing them because of their handicap?

Oh, but wait: an unborn child is not, under the law, a handicapped person; he is only a growth that has the potential to become a person. He has no rights, and therefore killing him is not an act of discrimination against a handicapped child, but the excision of a deformed growth. The rights of the handicapped, and the fact that they are killed almost routinely, are irrelevant.

This, though, might not be a position anyone wants to take. After all, seven states–Arizona, Kansas, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and South Dakota–ban sex selective abortions as acts of gender discrimination. It is against the law in those states to terminate an unborn female child because you wanted a son (or presumably to terminate a male because you wanted a daughter). Arizona also bans abortions based on the race of the unborn child as being racially discriminatory. To say that the unborn Down Syndrome child has no rights that can be protected from discriminatory abortion (that is, abortion based on the fact that the child will be born handicapped) is to say that the unborn daughter or son, or the unborn mixed race baby, has no rights and can be killed solely for being the wrong sex or the wrong race.

There is a degree to which the laws are irrelevant, like restrictions on job terminations: you cannot fire an employee for attending a union organization meeting, or for being homosexual, or for reasons of race or religion–but you can fire an at-will employee for no reason at all, so you simply have to avoid saying that any of these factors led to the decision. In the same way, a woman can terminate a pregnancy without giving a reason for doing so; she just cannot say that the reason is because of the gender, the race, or the genetic disability of the child. In practical terms the only thing they limit is our ability to be frank about our motivations.

Even so, these laws force us to face a fundamental aspect of our attitude toward abortion. Should a mother be able to decide that she wants to abort a child because the child’s medical condition will result in the child having a less than fully normal life? Does that reflect a reasonable desire to protect the child from its own illness, or is it making a discriminatory value judgment that it would be better not to live than to live with such a handicap? (How many handicapped-from-birth adults would rather never have been born than have been born handicapped?) Is it reasonable to say that the health of the mother would be threatened by the birth of a handicapped child in a greater way than it would be by the birth of a normal child, or by an abortion? If so, is it also reasonable to say that the health of the mother would be threatened by the birth of a daughter when she wanted a son, or a son when she wanted a daughter, or by a mixed-race child instead of a pure-race child?

We have stretched the concept of “health of the mother” far enough that it amounts to “I don’t want a child, and therefore it would be unhealthy for me to have one.” How much further does it have to stretch to be, “I don’t want a handicapped child,” “a mixed-race child,” “a daughter”? It seems to me that that is not a very far stretch at all–which means either we have already stretched it too far, or we have to accept that sex-selective abortions, abortions of the genetically handicapped, and race-based abortions are all as good a reason as any other, and do not constitute discrimination against a person, because there is no person here and the mother has been given the power to decide whether there will ever be one.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]