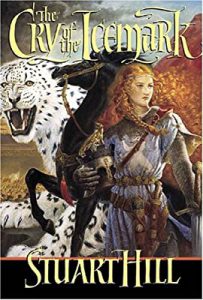

This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #368, on the subject of In re: Cry of the Icemark.

This was originally published at Gaming Outpost, preserved by the Wayback Machine, and republished here.

To say that Cry of the Icemark is a book for adolescent girls is not to insult it; I am sure that the author, Stuart Hill, intended this as his audience, and that Scholastic Books published it with their peculiar target market in view. It still qualifies as a fantasy novel, of sorts, and having taken the time to read it I now offer my thoughts on it.

For me, not a member of the target audience, the book took a somewhat slow start. The cultures which were borrowed wholesale to supply the backgrounds of the characters were too thinly veiled, and the religions both too recognizably real and too dimensionally shallow. Despite the fact that the thirteen-year-old heroine battles a powerful werewolf in the first chapter, I felt that everything was predictable. She loses that battle, incidentally, but the werewolf is apparently impressed by the courage with which she surrenders to face death, and lets her live.

That combination of courage and the willingness to accept that people who are different are still people become the real strengths of Thirrin Freer Strong-in-the-Arm Lindenshield. As her fourteenth birthday dawns, she has befriended the king of the werewolves and a young warlock in the woods, a boy a year older than her with whom an appropriate amount of sexual tension is built. The very Norse northern kingdom is threatened by an enemy to the south, a vast empire which takes Rome and infects it with the rationalism of the enlightenment. This, to my mind, was the strongest element in the story, that Thirrin’s world is filled with spirits and legendary creatures come to life, and the enemy invading her country is certain that all such myths are superstitions to be ignored or explained by some other means. It thus becomes a battle between those who believe in the supernatural reality around us and those who reject everything that science cannot explain, and we find ourselves rooting for the supernaturalists.

At first, the book seems to be broad-minded in its approach to its religious concepts. Thirrin and her father are clearly Odinites, followers of a religion that leads them to put their lives on the line for the sakes of their people, to see falling nobly in battle as glorious even if it is defeat. Her tutor from the south, Maggiore, is rather agnostic about all such things, but not to the point of rejecting them outright. The boy from the woods, Oskan, son of one of the most revered of the witches (there is some teasing about the never-revealed identity of his father), is a sort of Druidic Wiccan, worshipper of the Goddess and skilled in the craft of the woods, including the language of the werewolves. When we eventually meet Thirrin’s maternal relatives (her mother died when she was young), they follow a Greek religion focused on matriarchy. This cooperation of various faiths is interesting enough; however, only Oskan has any real power in the story, and by the end of the book there is a tacit understanding that Oskan’s religion is the one everyone respects, whatever they may say formally.

As Thirrin turns fourteen, the empire to the south invades. Winter is almost upon the land, and her father Redrought Strong-in-the-Arm Lindenshield, Bear of the North, King of the Icemark, is surprised that the famed and undefeated General Scipio Bellorum is sending a force into his territory so close to the snows–which are delayed, creating the real danger that Bellorum’s forces could crush the resistance at the border and lay seige to the capital before anything else could be done. Redrought places the safety of his people in the hands of his daughter, adding Wildcat of the North to her titles, and instructs that they flee yet farther north to the cities held by her mother’s kin where her aunt rules as their vassal. He then leads the bulk of his army against the invaders. His force is slaughtered to a man, but not before destroying the advance guard of his enemy and holding the border long enough for Thirrin to evacuate the capital. News and proof of the death of her father reach her eventually, making her Queen of the Icemark, responsible to save her land and her people from the powerful invaders.

Thirrin is as good a fighter as any man in the kingdom, and sometimes an inspired tactician, but her true strength proves to be uniting very divided people. Her initial encounter with the werewolf is reinforced by a kindness she shows him, and this forges an alliance between the Icemark and its hidden residents. Thanks to Oskan Witch’s Son she forges alliances with the Oak King and the Holly King who rule the forests of the north, and then she gains the support of her mother’s kin. This, though, is just the start. Her courage and character carry her to the realm of the Vampire King and beyond that to the northernmost regions of the world where the Giant Leopards do battle against the Ice Trolls, and are surprised to discover that the two-legged creatures in the southern lands who can speak in their language are more than myth. Humans and cats return to the capital city just as the roads are opening, and so are able to fortify it against the southern army and make their stand there.

The details of the battle are interesting, laced with magic and medieval combat. Thirrin and her forces hold their own while awaiting the arrival of reinforcements from their allies; Scipio Bellorum presses his advantages while explaining away anything that does not fit his enlightened view of reality. Each side takes its losses, but the sense is constantly present that Bellorum’s resources are nearly inexhaustible and he can afford to fight this as a war of attrition. Everything hangs on whether the vampires, ghosts, and werewolves will arrive before the city falls. The invader also proves that he is without honor but willing to take advantage of the honor of his enemy, offering to face Thirrin in single combat to decide the outcome, and then fleeing and failing to accept defeat when he has been critically wounded.

There is a degree to which the climactic battle is brilliant, but I saw it coming. Bellorum recognizes that the moon will be full, providing ample light for battle, and believes that a battle at night will prey upon the superstitions of the primitive barbarians he faces. Thirrin and her people think nothing of superstitions, only of the realities of the supernatural world around them, and so this does not have the impact Bellorum hopes. However, I suspect my readers see the flaw in Scipio’s plan and the intended surprise that the author brings at this point, when the battle is fought on the night of the full moon. Suffice it that by the time she turns fifteen, Thirrin Freer Strong-in-the-Arm Lindenshield, Wildcat of the North, Queen of the Icemark, has routed and eviscerated the greatest army in the world, and established peace in her kingdom.

Overall the book was satisfying, and certainly so when viewed as a children’s book. It is not so well crafted as the Harry Potter series, and the inconsistencies about the religious beliefs embraced by Thirrin detract from it. However, it was a pleasant read with some excellent battle accounts, clever ideas in magic, and a delightful core character group that made it worth the time.