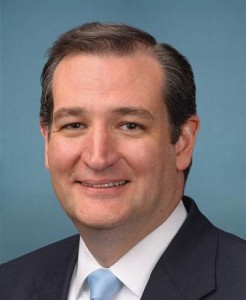

This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #41, on the subject of Ted Cruz and the Birther Issue.

The unabashedly liberal Huffington Post has reported that a Texas attorney has filed suit against Ted Cruz, claiming that the Republican United States Senator from Texas is not eligible to be President of the United States because he is not a “natural born Citizen” as required by the Constitution.

This is ground we covered in detail quite a few years ago; in fact, it was this issue that launched our political writing at The Examiner–only then the object was Barrack Obama. We have preserved those articles as The Birther Issue elsewhere on this site, and we’ll look at that.

The problem for Cruz is that he was not born in the United States. People argued whether Barrack Obama was or was not born in the United States, and whether the birth certificate published by the White House asserting a Hawaiian birth was in fact a forgery. The issue this time is not whether or not he was born in the United States–it is clearly established that he was born in Canada, to a mother who is incontrovertibly a United States citizen, and a Cuban-born father who fled to the United States and became a Canadian citizen a few years after the birth of his son Ted, then became an American citizen just over a decade ago.

Thus the question is whether Ted Cruz is a “natural born” United States citizen as required by the constitution, based on the fact that his mother being a United States citizen gave him U. S. citizenship at the moment of his birth, or whether he is not “natural born”, based on an interpretation of that phrase that requires that the President was actually born in these United States. It is a perennial issue–before Cruz of course it was raised concerning Obama, but it has also been raised in connection with Mitt Romney (born in Mexico to American parents), John Cain (born to a U. S. military family stationed on the U. S. military base in the Panama Canal Zone), Mitt’s father George Romney (born to U. S. citizen parents in self-imposed exile in Mexico), Barry Goldwater (born in the United States Territory of Arizona before it became a State of the Union), and quite a few others. In many of these controversies, scholars have asserted that the Supreme Court has never said what the Constitution means by the words “natural born citizen”.

They are only half right.

In United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898), the Supreme Court addressed a citizenship case. In that case, they cited Dicey’s Digest of the Law of England with approval, quoting that

“Natural-born British subject” means a British subject who has become a British subject at the moment of his birth.

They then quoted from a case which cited Blackstone to the effect that

a person who is born on the ocean is a subject of the prince to whom his parents then owe allegiance….

It seems quite evident that Wong Kim Ark asserted that “natural born citizen” of the United States meant no more and no less than that at the moment of birth the individual was a United States Citizen–something that clearly applied to Obama, both Romneys, and Cain, at least. By the standard set forth by Dicey and Blackstone cited by the Supreme Court in Wong Kim Ark, because Mrs. Cruz was a United States Citizen at the time that her son Ted was born, Ted Cruz is a natural born citizen of the United States, and eligible to become President of these United States.

So what’s the problem? How can anyone say that the Court has not decided this question, if the court has decided it?

The problem is that the court stated that, but did not decide it. It falls into the category of what is called “dicta”–statements made by the court that are not directly relevant to the decision in the case but express what the court probably would decide about such an issue. Wong Kim Ark had nothing to do with presidential eligibility. It was about the California-born son of Chinese citizens refused admission to the country on returning from a visit to foreign relatives abroad because of a California anti-immigration law, and decided only that the child of anyone born in the United States to parents who were legally present in the United States at the time of that birth was a citizen of the United States at the moment of his birth. The cited passages in Dicey and Blackstone were part of a more general discussion that supported that conclusion, and although they clearly support the conclusion that anyone who was a citizen at the moment of his birth, wherever born, is a natural born citizen, the decision of the case technically only supports its own conclusion, that anyone legally born on United States soil is a United States citizen at that moment.

So technically the critics are right: the issue has never been “decided” because it has never been raised as such. However, the reasoning of Wong Kim Ark leads inexorably to the conclusion that people in the position of any of these politicians, including Ted Cruz, are “natural born citizens” under the intended meaning of the Constitution, and eligible to be President of the United States, and there is no reason to imagine that the Supreme Court would decide otherwise given that precedent.

Cruz is right: the issue which did not matter half a year ago is being raised now because he has become a serious contender for the Republican nomination. It is not, and should not be regarded, a real issue.

[contact-form subject='[mark Joseph %26quot;young%26quot;’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Website’ type=’url’/][contact-field label=’Comment: Note that this form will contact the author by e-mail; to post comments to the article, see below.’ type=’textarea’ required=’1’/][/contact-form]

So, if I understand the logic correctly, a child of illegal immigrants to the US, born in the US does not automatically get citizenship? Rather they should have the citizenship of their parents at the time? Or are there other rulings in place that make them citizens?

Oh, and it’s McCain, not Cain. Somewhat of a Freudian slip there.

Eric–That’s actually been bothering me for a while. The problem is that the rules actually can change, based on legislation. At one time someone born abroad was a citizen if his father was a citizen, but not if only his mother was a citizen (in which case the father’s citizenship controlled). The statute that has controlled since about 1952 (if I remember the date aright) made it so that you were born a citizen if either parent was a citizen.

I have been thinking for a while that I should have gone over that list more carefully when I was doing the articles half a decade ago, because I don’t know whether it says something about citizenship by birth. The 14th Amendment gave citizenship to everyone legally born in the United States (to prevent former slave owners from depriving freed slaves of citizenship) but it’s not clear that it applies to illegals. (It does not, for example, apply to the children of foreign diplomats–our Multiverser player friend Graeme Comyn was born in Philadelphia to a Canadian mother and a British father who was a member of the British diplomatic core, and he has to explain every time he crosses the border that he is not an American citizen despite being born in this country.)

So maybe if I feel a bit better in a couple days I’ll track that down again and see what it says.

O.K., the statute is at https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1401 and it begins

*****

The following shall be nationals and citizens of the United States at birth:

(a) a person born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof;

(b) a person born in the United States to a member of an Indian, Eskimo, Aleutian, or other aboriginal tribe:

Provided

, That the granting of citizenship under this subsection shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of such person to tribal or other property;

*****

I think that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” automatically excludes diplomats. It probably also excludes native Americans born on tribal lands/reservations, maybe also those born in hospitals or other facilities outside tribal lands, which is why there is a specified statement for that.

But I think most courts would take “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” to include those born here illegally (we couldn’t deport them were they not subject to jurisdiction). You would have to make a significant argument to the effect that this clause actually means compliant with that jurisdiction and thus does not apply to the children of illegals, and I don’t know that I would buy it. (I’m sure there’s a supporting argument somewhere, but I haven’t thought of it.)

However, note that there is a presumption here that Congress is authorized by the Constitution to create such a definition, and that means it would at least be plausible to introduce legislation that rephrased that to include only those born to parents legally within the United States. I don’t think you’d get it passed, though.