This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #305, on the subject of The Cross Case: Supreme Court Sours on Lemon.

I have been watching for this case since it hit the circuit court, and so was pleased to see that the Supreme Court had decided it. It seems on one hand to be a simple question: is a century-old war memorial in the shape of a forty-foot cross originally built by private citizens but for half a century maintained on public land at public expense a violation of the “establishment” clause, that is, a constitutionally impermissible promotion of a particular religion by the government? That’s the question; yes or no?

So imagine my surprise to discover that although Justice Alito managed to write a seven-to-two majority opinion that said no (that is, the cross can stay), there were five concurring opinions (a concurring opinion is one that agrees with the conclusion but not with all the reasoning) plus a dissent. So how is there so much confusion over so simple a question?

At the time of this writing, I was unable to find the official Supreme Court PDF online; however, Justia has it in an easy-to-access form. The Court combined two cases into one, so the title reads

THE AMERICAN LEGION, et al., PETITIONERS

v.

AMERICAN HUMANIST ASSOCIATION, et al.; and

MARYLAND-NATIONAL CAPITAL PARK AND PLANNING COMMISSION, PETITIONER

v.

AMERICAN HUMANIST ASSOCIATION, et al.

A lot of the trouble revolves around what’s been called the Lemon Test, named for Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971), in which the court articulated a three-part test for whether something violated the establishment clause. The short version is:

- Does the action/activity have a secular purpose?

- Is the principle or primary effect one that neither advances nor inhibits religion?

- Does it avoid fostering an excessive government entanglement with religion?

By these three questions all such cases were supposed to be answered.

Let’s get some backstory.

Just after World War I, a citizens group in Bladensburg, Maryland wanted to honor the forty-nine men from their community who died in that conflict. Quite a few of the fallen in that war were never returned, and more were never identified. The monument would serve as a surrogate grave for them, for their families to visit, and as a recognition of the service of so many others. They hired an architect/sculptor, who designed a large Latin Cross, modeled on the crosses that had been used as temporary grave markers for the over one hundred thousand Americans buried in European graveyards. (The Star of David was also used for such markers, but only about five percent of American casualties were Jewish, so crosses dominated the photos that came home and were emblazoned in the minds of the mourners.) The citizens group raised money through donations, but ran out before completing the work, so the American Legion took over, adding their emblem to the cross, finishing the work, and maintaining it at their own expense into the early 1960s. At that time, actions were taken to transfer the ownership of the property to the Maryland Parks Department, in part because the road around the monument had become a major traffic problem, in part because the American Legion was no longer able to afford it, and in part because the State wanted to expand the surrounding area into a memorial park with monuments for all the other wars. Since then the monument has been maintained by state funds. However, a few years back the American Humanist Association filed suit claiming that the cross was offensive and an impermissible endorsement of the Christian religion. They wanted it removed, or demolished, or at the very least stripped of the crosspiece so it would be an obelisk instead of a cross.

The Federal District Court applied the Lemon test and sided with the park service, stating that the primary purpose of the cross was to honor the dead of World War I, and there was no evidence that any religious purpose was intended in its design or its present maintenance; any impartial observer who knew the history of the monument would conclude that it was not about promoting Christian faith, but about honoring the war casualties. A three-judge panel of the Circuit Court, however, disagreed in a split decision, again applying the Lemon test but asserting that the cross was so tied to Christian belief that anyone seeing it would think it was an emblem promoting that religion. The full court declined to review the case en banc (that is, all the judges), and the Supreme Court granted certiorari (or cert., agreeing to hear it).

Justice Alito wrote that there were many problems with applying Lemon, and that since the the test has a lot to do with motivations and intentions it is particularly difficult to apply the case to situations with deep historic roots. It can’t be said that those who originally erected the monument had a religious purpose in view. He cites other situations in which crosses are used as an emblem that do not have a religious purpose, notably among them the International Red Cross, whose red cross on a white field was designed to call to mind the white cross on a red field that was the flag of the neutral country Switzerland, and so marking the deliverers of medical care as neutral. So, too, the crosses that dotted graveyards throughout Europe had become an image of the fallen in that war, popularized alongside the poppy even more by the poem In Flander’s Field. Shortly after the war the same emblem became the basis for the national congressional medals known as the Distinguished Cross and the Navy Cross. There was no reason to suppose that the original designers of the cross intended it to have any greater religious significance than that which is attached to any grave marker. Indeed, one of the members of the committee which began the work and approved the design was Jewish. Further, there is no evidence of bias or prejudice, sectarian or otherwise. At the dedication ceremony, a Catholic Priest opened with an invocation, a politician gave the keynote address, and a Baptist minister gave the closing benediction. Although racial tensions were high in the country and the Ku Klux Klan held a rally within ten miles of the site within a month of the dedication, black and white soldiers were listed together on the plaque. To claim that the original intention was religious is to read our own ideas into their situation; we cannot do that. Further, he argued, the fact that the monument has been there for almost a century means it has taken many other significances, historical and cultural. We might think there is a religious significance to it as well, but it is a relatively small part of a memorial that has been part of the community for so long. Besides, to destroy or deface it would appear to be an act against religion, not an act furthering religious neutrality.

The opinion did not overturn Lemon; it simply said that in dealing with matters steeped in history, it was generally impossible to know the motivations of those who made the original decisions, and so Lemon was rendered useless in such cases.

Justice Gorsuch in the main agreed, but went further. Lemon, he said, was useless as a test. Case law demonstrates that a court using the test can reach any conclusion it wants. More pointedly, the notion of the response of a reasonable observer (whether a reasonable observer would think that the purpose was primarily religious) has created an “offended observer” status, that someone can file suit against an action on the grounds that it offends him. This, Gorsuch argues, is not real injury and the Constitution gives no basis for anyone to sue without real injury. Overturning Lemon and getting rid of its test would resolve much of the confusion in the courts and mean in the future cases like this, in which someone claims to be offended by the sight of a supposedly religious object, would be dismissed perfunctorily.

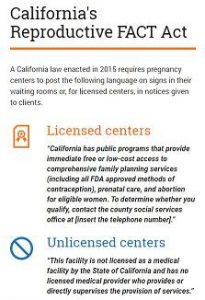

Justice Thomas agreed with that, but went further. The Establishment Clause, he observed, begins “Congress shall make no law”. He explains what kinds of laws had existed that were eliminated, but asserts that the protection has nothing to do with actions that are not based on laws made by Congress. He suggests that one might apply the I Amendment to the States by virtue of the XIV Amendment, but even so the original purpose of the Establishment Clause was to forbid legislative actions compelling citizens to support a specific church or denomination. Local creches, non-sectarian thanksgiving services, opening invocations and closing benedictions, and memorials to the dead are not covered by this, as they are not compulsory and in the main are not legislative acts. Lemon, he asserts, should be overturned because it goes far beyond what is Constitutional.

Justice Kagan also wrote a concurring opinion, agreeing with nearly all of Justice Alito’s opinion but for two sections. The important disagreement is that she asserts that Lemon, with its focus on purposes and effects, is still very valuable even though it does not resolve every Establishment Clause problem, and she would retain it. Her lesser disagreement is that Justice Alito suggested that history would play an important part in Establishment Clause analysis, which she does not reject entirely but does not wish to see embraced as a principle of law. She agrees, though, that it might be important to consider whether long-standing monuments, symbols, and practices reflect respect for different views and tolerance, with an honest effort to achieve non-discrimination and inclusivity, and a recognition of the important role that religion plays in many American lives.

Justice Kagan also agrees with the concurrence written by Justice Breyer, who has long said that no one test works for all Establishment Clause cases, but that in each case the court has to consider the purposes of the clause, “assuring religious liberty and tolerance for all, avoiding religiously based social conflict, and maintaining that separation of church and state that allows each to flourish in its “separate spher[e]”. He says that the majority opinion is correct that there is no significant religious importance to the Bladensburg Cross, and that its removal or destruction would signal a hostility toward religion against the Establishment Clause traditions. However, he objects to any sort of “history and tradition test” that might permit religiously-biased memorials on public lands in the future.

That, apparently, is a suggestion in Justice Kavanaugh’s concurrence. He fully joins the majority opinion, but emphasizes the importance of reviewing history and tradition in such cases. He suggests that the Lemon test has proven useless and is never really used by the Supreme Court. He also expresses sympathy for those, particularly Jews, who feel alienated by the cross, which he says must be recognized as a religious emblem. The fact that it is a religious emblem does not mean the government cannot maintain it–but the government does not have to do so, and other branches of the government could take action to remove the cross or transfer its ownership and care to a non-governmental entity. The objectors do have recourse to the political process if they wish to pursue this; what they don’t have is a court decision declaring that the cross cannot be maintained by the State.

Which leaves Justice Ginsberg’s dissent, joined by Justice Sotomayor.

Ginsberg maintains that the Latin Cross, defined as one in which the lower upright is longer than the other three branches, has always been recognized as a Christian symbol, and has never had a secular meaning or application. (This in contrast to the Greek Cross, in which the four branches are equal.) The Bladensburg “Peace Cross” is thus offensive to anyone of any other religion or of no religion. Marshaling evidence that even in the aftermath of World War I the cross was identified by the government as a sectarian symbol to be put on the graves of all Christians and of any persons not known not to be Christian (in case they were), with Stars of David placed on all graves of soldiers known to be Jewish. (Those who were known not to be either could, at the family’s request, have a plain stone, be transported home, or be interred in a private cemetery overseas with a headstone of their choice.) There has never been a case in which a Latin Cross was identified as a non-sectarian emblem of death, and historically it has been regarded as conveying the message that Christians are saved and all others are damned–an offensive message to all those others.

While Ginsberg’s claim is well-supported, it is not clear that the modern cultural view of crosses as memorials perceives them as specifically Christian. It comes to me that many graves of pets are marked with crosses, but no Christian denomination of which I am aware supports the theological belief that animals can be Christian, The Vicar of Dibbley notwithstanding. (The eternal destiny of animals is not something the Bible tells us, which makes sense, as C. S. Lewis would have said, because it’s not actually something we need to know.) Crosses are also frequently used in decorative graveyards such as in Halloween displays. To many, the cross says “grave marker” much more than it says “Christian”.

I can’t say that everyone perceives such memorials as non-sectarian, but I do think that over time they have become more so. It appears that the Court, in the main, agrees with that: memorials using crosses in their imagery have become non-sectarian by their use over time, and the Bladensburg Cross far more represents the fallen of World War I and, since its rededication in 1985, all the American casualties of all our wars. Lemon has not been overturned, but it has been significantly limited in its application in the future.

The Peace Cross stands.