This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #251, on the subject of Voter Unregistration Law.

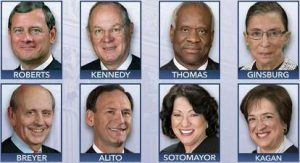

As I was reading the majority opinion of Husted, Ohio Secretary of State v. A. Philip Randolph Institute et al., 584 U. S. ____ (2018), I wondered how anything so obvious could possibly have been a controversial five-to-four decision along ideological lines.

Then I read the dissent, and realized that this was not a simple case, and it is not a mystery why it kept flip-flopping its way up the ladder to the Supreme Court. Ultimately, though, it comes down to whether when we read the statute we read it as and or or.

Here’s the background. Prior to 1993–which for some of you seems like ancient history, but is really not that long ago–state governments had a lot of ways of removing voters from the registration lists so that they couldn’t vote. One of the most egregious was that if you missed an election one year the system concluded that you had either moved or died, and removed your name from the lists with the result that if you arrived the next year you would discover that you weren’t registered and couldn’t vote. To remedy this, the Clinton administration passed the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), which both required states to maintain current voter registration lists (which included removing ineligible voters) and limited how they could remove persons from the list. It was tweaked a bit in 2002 when Bush (the second Bush) signed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA), which attempted to clarify some of the statements in the previous law. Ohio has a system which it maintains is consistent with the requirements of those laws, by which it removes persons from the voter lists based on a multi-step process. The majority agrees; the dissent disagrees.

It will help significantly to look at the statutes themselves, large portions of which Justice Breyer appends to his dissenting opinion.

The focus of discussion begins with §8(b) of the NVRA

Any State program or activity to protect the integrity of the electoral process by ensuring the maintenance of an accurate and current voter registration roll for elections for Federal office—

(2)

shall not result in the removal of the name of any person from the official list of voters registered to vote in an election for Federal office by reason of the person’s failure to vote.

The HAVA modifies that to say solely by reason of the person’s failure to vote, probably because of confusion with §8(d). That section lays out a somewhat complicated process for verifying that a voter has moved out of the voting district in which he is registered. The simple way is for the registrant to confirm in writing that he has moved. The law recognizes that a lot of people won’t do that, and so provides an alternate method involving sending (by forwardable mail) a postpaid return card which permits the recipient to respond confirming that he still lives at the stated address or that he does not. If the card is returned, the registrar of voters accepts the statement as true and the matter is resolved. If the card is not returned and the voter does not vote in the next two federal elections he may be removed from the list. (Federal elections occur every other year because terms for The House of Representatives are two-year terms.)

At issue is under what circumstances such a card can be sent. §8(c) specifies that if the state obtains change of address information from the Post Office, it must verify that information by following the procedure just outlined. However, §6(d) specifies that the same confirmation process should be used if voter registration materials are sent to a registrant by non-forwardable mail and are returned as undeliverable. It thus appears that there is more than one way by which the registrar of voters might have reason to believe that a voter has left the voting district, triggering the §8(d) process.

Here is where it gets tricky.

Ohio’s system works like this. If a registered voter fails to vote for two consecutive years, or to engage in any other voter-related activity such as signing petitions, a forwardable post-paid return card is sent to that voter’s registered address. If the card is returned, that’s the end of the matter. If the the card is not returned, Ohio gives four additional years (covering at least two Federal elections at least one of which is a Senate race and one a Presidential race) to vote or engage in other voter activity, after which the non-voting voter is removed from the voter registration list.

The majority says that this is a reasonable method, perfectly in keeping with §8(d). The failure to vote alerts the registrar of voters that this person might not live here anymore, and because the person fails to respond to the return card confirming their presence and at least two additional Federal elections pass in which they do not vote, they can be removed. The majority takes the language in §8(b)(2) to put an end to the practice of removing voters solely for failure to vote by requiring the confirmation process of §8(d). They note that some states send such cards regularly or randomly to confirm addresses, and Ohio’s system complies with their understanding of the §8(d) process.

The dissent says that such cards are for confirmation of information gained by some other means, such as from the Post Office (§8(c)) or through a different mailing verification process (§6(d)). They assert that the point of §8(b)(2), that no one should be removed soley for failure to vote, means that failure to vote cannot be the trigger to send the returnable card. They claim that the §8(d) confirmation process must be triggered by something other than failure to vote.

Perhaps the strongest point in favor of the dissent’s position is that one of the stated purposes of these two laws is to increase voter registration and prevent eligible voters from being removed from the list inappropriately. The fact that someone doesn’t vote for a couple years does not mean they are no longer in residence in the district, and the fact that they fail to return a postpaid card confirming that they are present is not a particularly telling confirmation of anything. As the dissent argues, the majority of people probably won’t bother returning such a card.

The majority points to the statute on that, noting that both the Federal legislature and the State of Ohio believed that the non-return of such a card would be an adequate indicator that the person has moved. The argument is that a person who does not vote and does not return the card is not being removed “solely” for failing to vote, but for failing to vote over the course of six years and failing to return a confirmation card. The question is whether the state can send the confirmation card based on two years of failure to vote, or whether that constitutes removing them “solely” for failing to vote.

In favor of the majority, though, if §8(b)(2) means what the dissent claims it means, it is poorly worded. The majority reading is not at all awkward or implausible, and the Ohio system appears to fit the §8(d) requirements with room to spare. Despite the ranting of the minority, the majority opinion does seem the more natural reading of the text.

The upshot is that the Ohio system stands, and many other states with similar systems will not be challenged. Removal from the voter rolls solely for failure to vote is not permitted, but it can be the trigger that leads to an inquiry by mail as to whether the voter still lives in the district.