This is mark Joseph “young” blog entry #325, on the subject of The 2019 Recap.

Happy New Year to you. A year ago I continued the tradition of recapitulating in the most sketchy of fashions everything I had published over the previous year, in mark Joseph “young” web log post #278: The 2018 Recap. I am back to continue that tradition, as briefly as reasonable, so that if you missed something you can find it, or if you vaguely remember something you want to read again you can hunt it down. Some of that brevity will be achieved by referencing index pages, other collections of links to articles and installments.

For example, that day also saw the publication of the first Faith in Play article of the year, but all twelve of those plus the dozen RPG-ology series articles are listed, described, and linked in 2019 at the Christian Gamers Guild Reviewed, published yesterday. There’s some good game stuff there in addition to some good Bible stuff, including links to some articles by other talented gaming writers, and a couple contributions involving me one way or another that were not parts of either series. Also CGG-related, I finished the Bible study on Revelation and began John in January; we’re still working through John, but thanks to a late-in-the-year problem with Yahoo!Groups that had been hosting us we had to move everything to Groups.IO, and I haven’t managed to fix all the important links yet.

At that point we were also about a quarter of the way through the novel Garden of Versers as we posted a Robert Slade chapter that same day, but that entire novel is indexed there, along with links to the web log posts giving background on the writing process. In October we launched the sixth novel, Versers Versus Versers, which is heating up in three chapters a week, again indexed along with behind-the-writings posts there, and it will continue in the new year. There are also links to the support pages, character sheets for the major protagonists and a few antagonists in the stories. Also related to the novels, in October I invited reader input on which characters should be the focus of the seventh, in #318: Toward a Seventh Multiverser Novel.

I wrote a few book reviews at Goodreads, which you can find there if you’re interested. More of my earlier articles were translated for publication at the Places to Go, People to Be French edition.

So let’s turn to the web log posts.

The first one after the recap of the previous year was an answer to a personal question asked impersonally on a public forum: how did I know I was called to writing and composing? The answer is found in web log post #279: My Journey to Becoming a Writer.

I had already begun a miniseries on the Christian contemporary and rock music of the seventies and early eighties–the time when I was working at the radio station and what I remembered from before that. That series continued (and hopefully will continue this year) with:

- #281: Keith Green Launching

- #283: Keith Green Crashing

- #286: Blind Seer Ken Medema

- #288: Prophets Daniel Amos

- #290: James the Other Ward

- #292: Rising Resurrection Band

- #294: Servant’s Waters

- #296: Found Free Lost

- #299: Praise for Dallas Holm

- #302: Might Be Truth and the Cleverly-named Re’Generation

- #304: Accidental Amy Grant

- #312: Produced by Christian and Bannister

- #315: Don Francisco Alive

- #324: CCM Ladies of the Eighties

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, it is evident that the music dominated the web log this year. In May I was invited to a sort of conference/convention in Nashville, which I attended and from which I benefited significantly. I wrote about that in web log post #297: An Objective Look at The Extreme Tour Objective Session. While there I talked to several persons in the Christian music industry, and one of them advised me to found my own publishing company and publish my songs. After considerable consideration I recognized that I have no skills for business, but I could put the songs out there, and so I began with a sort of song-of-the-month miniseries, the first seven songs posted this year:

- #301: The Song “Holocaust”

- #307: The Song “Time Bomb”

- #311: The Song “Passing Through the Portal”

- #314: The Song “Walkin’ In the Woods”

- #317: The Song “That’s When I’ll Believe”

- #320: The Song “Free”

- #322: The Song “Voices”

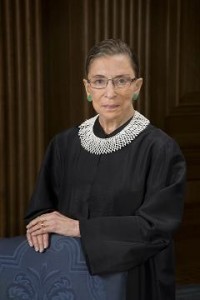

I admit that I have to some degree soured on law and politics. Polarization has gotten so bad that moderates are regarded enemies by the extremists on both sides. However, I tackled a few Supreme Court cases, some issues in taxes including tariffs, a couple election articles, and a couple of recurring issues:

- #282: The Fragility of Unborn Life Argument

- #287: They Can’t Take Your Car

- #289: Stifling Lozman’s Protected Speech

- #295: Does China Pay Tariffs?

- #298: Taxing Corporations

- #305: The Cross Case: Supreme Court Sours on Lemon

- #308: Assembly Candidate Edward Durr Interview

- #309: Racially Discriminatory Ticketing

- #321: The 2019 New Jersey Election Ballot

I was hospitalized more than once this year, but the big one was right near the beginning when the emergency room informed me that that pain was a myocardial infarction–in the vernacular, a heart attack. Many of you supported me in many ways, and so I offered web log post #285: An Expression of Gratitude.

Most of the game-related material went to the RPG-ology series mentioned at the beginning of this article, and you should visit that index for those. I did include one role playing game article here as web log post #303: A Nightmare Game World, a very strange scenario from a dream.

Finally, I did eventually post some time travel analyses, two movies available on Netflix. The first was a kind of offbeat not quite a love story, Temporal Anomalies in Popular Time Travel Movies unravels When We First Met; the second a Spike Lee film focused on trying to fix the past, Temporal Anomalies in Time Travel Movies unravels See You Yesterday. For those wondering, I have not yet figured out how I can get access to the new Marvel movie Endgame, as it appears it will not be airing on Netflix and I do not expect to spring for a Disney subscription despite its appeal, at least, not unless the Patreon account grows significantly.

So that’s pretty much what I wrote this year, not counting the fact that I’m working on the second edition of Multiverser, looking for a publisher for a book entitled Why I Believe, and continuing to produce the material to continue the ongoing series into the new year. We’ll do this again in a dozen months.